Research in the Warner Lab examines interactions between organisms and their environments at several different levels of organization and across multiple life-history stages (from embryos to adults). By quantifying relationships between phenotypes and fitness, we aim to understand how natural selection has shaped the phenotypic variation and organismal responses that we observe. We use a variety of techniques (e.g., genotyping, radio-immunoassays, respirometry, mark-recapture experiments) and combine field and lab studies to gain a comprehensive understanding of adaptive evolution. Our research focuses on reptiles because these organisms have several characteristics that make them excellent models for addressing fundamental questions in evolutionary ecology.

|

Developmental plasticity and egg physiological ecology

Plastic responses of embryos to developmental conditions are nearly ubiquitous throughout life. Decades of research demonstrate that embryonic environments influence developmental patterns and offspring phenotypes in ways that impact fitness. Our research on this topic integrates lab studies of egg physiological ecology with release-recapture experiments in the field to understand how selection has shaped patterns of developmental plasticity. For example, we have shown that temperature and moisture conditions during egg incubation affects offspring body via their influence on developmental rate or yolk metabolism. These phenotypic effects, in turn, influence individual survival and/or reproductive success later in life. We have studied the fitness consequences of developmental conditions in several reptiles (e.g., jacky dragons, fence lizards, painted turtles), and most of our current focus is on the brown anole lizard. |

|

Adaptive significance of parental effects

Parental effects occur when the phenotype or environment of the parents (typically the mother) influence offspring phenotypes independent of, or interacting with, inherited genes. In other words, parental effects are a form of developmental plasticity that spans generations. Our research addresses how maternal environments (e.g., nutrition, social conditions, age) influence patterns of reproductive investment, and in turn, how investment impacts offspring phenotypes and fitness. We also evaluate the fitness consequences of maternal nest-site choice, which is a behavioral maternal effect that influences the environment that embryos experience during development. Research on this topic also incorporates aspects of sex allocation biology (i.e., the differential investment towards sons versus daughters) and parent offspring conflict (i.e., evolutionary conflict arising from parent/offspring differences in optimal investment). The brown anole lizard makes an excellent model for addressing these issues because they reproduce well in captivity and (like all Anolis lizards) females produce a single egg about once per week, which enables females to differentially invest into each offspring that they produce. |

|

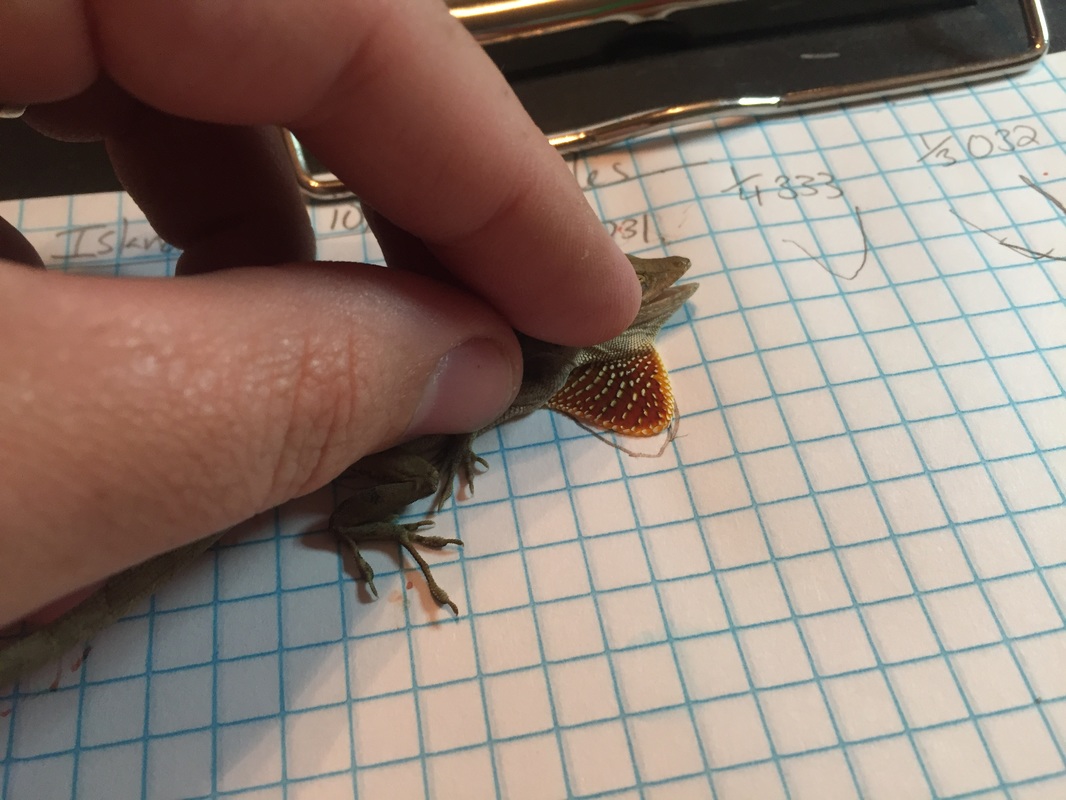

Phenotypic selection and experimental evolution in the wild

The potential for traits to evolve in response to natural selection depends largely on the strength, form and consistency of selection in nature. To quantify phenotypic selection in the wild, we have initiated a large-scale cross-generational study on several populations of brown anole lizards located on islands in Florida's Intracoastal Waterway. These islands provide an outstanding opportunity to assess spatial variation in selection and to assess the temporal consistency of phenotypic selection across generations. We have already manipulated population sex ratios on several islands to assess the effects of this important demographic feature on the strength and form of phenotypic selection. To compliment our lab-based studies, we have long-term plans to use these "replicated" islands to address how selection operates on maternal nesting behavior and embryo reaction norms for different phenotypes. In addition, we are examining how egg incubation environments influence how lizards use the different types of habitat on these islands. |

|

Evolutionary ecology of temperature-dependent sex determination

In many organisms, the temperature that embryos experience during development determines offspring sex. This temperature-dependent sex determination (TSD) is a form of developmental plasticity and appears multiple independent times across the reptile phylogeny. The numerous independent origins of TSD raises many questions about the adaptive significance of this atypical sex-determining system. Our work is focused on understanding the fitness consequence of TSD by assessing how developmental temperature impacts the survival and reproductive success of sons versus daughters. We have already shown that egg incubation temperature affects sex-specific fitness in a short-lived lizard species from Australia (the jacky dragon); in this species TSD enhances fitness because it enables each sex to develop under their respective optimal thermal environment. We are continuing to address related topics in local populations of yellow-bellied slider turtles and on invasive African rock agama lizards. Our work also evaluates the physiological and behavioral mechanisms that enable sex ratios to adjust to climatic variation, and how regional climate and habitat change will impact nest temperatures and primary sex ratios. |

|

Urban adaptation and invasion biology

The ecological and economic impacts of invasive species are a growing, cosmopolitan concern. Currently, urban land area is increasing at a rate potentially twice that of human population growth, which leads to the encroachment of plants and animals into urban areas. The Anthropogenically Induced Adaptation to Invade (AIAI) hypothesis predicts that populations of organisms adapted to urban areas may be primed to become successful invaders of similarly disturbed habitats elsewhere. This is because urban areas in different parts of the world likely impose similar challenges when compared to natural areas of the same regions. Research in the Warner Lab will provide novel insight into the fundamental causes of biological invasion by exploring the evolutionary consequences of novel environments on an oft neglected life-history period, embryonic development. Our aim is to better understand how organisms adapt and acclimate to human-disturbed habitat and how such changes may influence rates of naturalization and invasion. |